Getting oil and gas working for Africa

Ahead of African Oil Week, which is due to take place between 09 – 13 October 2023 in Cape Town, at the International Convention Centre, Wood Mackenzie considers how to get oil and gas working for Africa.

- Advertisement -

Africa is yet to see anything close to a full return on its massive oil and gas resources. With one-third of the continent – almost 500 million people – still having no access to electricity, ending energy poverty across Africa is among the planet’s most urgent challenges.

To address this, action is imperative to accelerate upstream investment across Africa and ensure a far wider share of its economic benefits. Giant discoveries in Namibia, FIDs (Final Investment Decision) in Angola and a bumper 2022 for new field start-ups all bode well, but can numerous other major projects across Africa secure the financing needed to move forwards?

- Advertisement -

Developing Africa’s huge natural gas reserves is essential not only for growing export revenues but also to support domestic economic growth and help the continent unlock its low-carbon energy potential. Can Africa find an economic solution for its gas riches?

- Advertisement -

As the Majors downsize across Africa, domestic independent operators are stepping up to champion the region’s oil and gas developments. But with mounting challenges around financing, carbon emissions and dominant NOCs (National Oil Companies), can these companies prosper?

Ahead of African Oil Week, which is due to take place between 09 – 13 October 2023 in Cape Town, at the International Convention Centre, Wood Mackenzie considers how to get oil and gas working for Africa.

Financing Africa’s oil and gas development

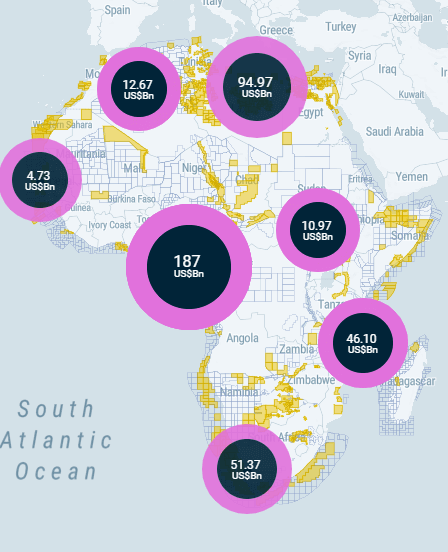

While African upstream investment is recovering, securing capital to develop the continent’s oil and gas resources remains a monumental challenge. Putting this into perspective, despite the region having the third-largest remaining resource base by region, over the next ten years we expect Africa to account for only 6% of global upstream investment. As a result, Africa’s production will decline from 12.4 million boepd in 2024 to 10.1 million boepd in 2033.

Reversing this needs action on three fronts. First, reducing costs and improving project delivery. There are positive developments here: Angola, Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria have led the way, and we expect 2023 to be a significant year for new production start-ups. African greenfield FIDs are also moving forward. Led by Angola, we expect four major greenfield projects reaching FID throughout the year. But more must be done, and cost inflation pressures will weigh on both operators and lenders at African projects that are often more expensive and complex to finance.

Second, the role of government. With high prices, governments’ default position will be to increase tax rates. This is likely to exacerbate the problem. A more enlightened approach would be to ease the tax take on new investment, as Nigeria and Angola have both done. Tax allowances for renewables to power upstream developments would be even bolder, showing a commitment to decarbonise Africa’s upstream industry and diversify into low-carbon technologies.

Third, investments in Africa must respond to the increasing regulations around sustainability. African upstream carbon intensity is amongst the highest globally, deterring buyers looking for low-carbon supply. African countries must tackle the major sources of upstream emissions – flaring, production and processing, and methane leakage – or risk an increasing number of IOCs (International Oil Companies) and lenders walking away.

Finding new avenues to gas resource development

With domestic gas markets non-existent in many countries, Africa’s major gas resource holders have historically looked to onshore LNG export projects for commercialisation. Most have been defined by high costs, low returns and long payback periods.

- Advertisement -

Alternative development solutions for their gas resource are therefore crucial for gas-rich nations throughout Africa and floating LNG (FLNG) is offering a differentiated pathway to gas monetisation.

The reasons are clear. After a stuttering start, FLNG’s lower capital costs combined with increased demand for quick-to-market LNG has again made FLNG an attractive proposition for developers, investors and off-takers.

Africa is at the centre of the current boom. Cameroon GoFLNG and Mozambique’s Coral Sul FLNG project blazed the trail, with projects in Mauritania/Senegal, Congo and Gabon following. FLNG is also under consideration in Nigeria and Namibia, and offers an alternative option for Mozambique’s troubled onshore Rovuma project.

Despite this bullish outlook, FLNG is not without risks. Concerns over cost blowouts, scheduling delays and security will need to be managed by developers of more than 20 mmtpa of African FLNG either under construction or considering FLNG as a development option.

A bigger challenge for Africa is developing gas for the domestic market. Despite the immense potential for gas to boost power generation and support economic growth, familiar issues around affordability and limited infrastructure continue to hold back capital investment.

The rise of the Africa’s independent operators

It is a sign of the increasing maturity of African independent operators that local players have the confidence to take on the development of their own natural resources. African independents are increasingly active, picking up assets from IOCs divesting non-core African portfolios.

We identify three drivers. First, the maturity of the Majors’ legacy African portfolios. With these companies under increasing pressure to focus on low-carbon, low-cost opportunities, divesting from late-life, carbon-intensive assets in locations including Nigeria, Gabon and Congo fits with their strategies.

Second, African governments are increasingly supportive of local independents accessing the region’s substantial resources. Favourable tax terms for new entrants and marginal assets have helped boost the emergence of African independents. Conducive regulatory environments in turn lead to greater economic diversification, job creation and growth in domestic industries. The Dangote refinery development in Nigeria, which is set to transform the regional oil products sector, is just one example.

Third, while financing remains a significant hurdle, African independents are increasingly demonstrating their ability to navigate above-ground challenges which have deterred IOCs from maximising the potential of their assets. A local “licence to operate” and partnerships with international investors are helping African companies access capital and the technical expertise required to acquire and develop assets.

Remaining African upstream investments by region

- Advertisement -