Danger on Red Sea splitting the global oil market in two

he global oil market is looking increasingly local as militant attacks in the Red Sea and surging freight rates make supplies from closer to home more attractive. A slump in tanker traffic through the Suez Canal is spurring the beginnings of a split, with one trading region centered around the Atlantic Basin and including the North Sea and the Mediterranean, and another encompassing the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and East Asia. There’s still crude moving between these areas — via the longer and costlier journey around the southern tip of Africa — but recent buying patterns point to disconnection. Across Europe, some refiners skipped purchases of Iraqi Basrah crude last month, according to traders, while buyers from the continent are snapping up cargoes from the North Sea and Guyana. in Asia, a jump in demand for Abu Dhabi’s Murban crude led to a spike in spot prices in mid-January, and flows from Kazakhstan to Asia are down sharply. Crude loadings from the US to Asia, meanwhile, plunged by more than a third last month from December, ship-tracking data from Kpler show. The fragmentation will not be permanent, but for now it’s making it tougher for import-dependent nations like India and South Korea to diversify their sources of oil supply. For refiners, it limits their flexibility to respond to rapidly changing market dynamics and could eventually eat into margins. “The pivot toward logistically easier cargoes makes commercial sense, and that will be the case for as long as the Red Sea disruptions keep freight rates elevated,” said Viktor Katona, lead crude analyst at data analytics firm Kpler. “It’s a tough balancing act choosing between security of supply and maximizing profits.” RelatedPosts From green hype to bailouts, the nickel industry has imploded Government drops 15% VAT on electricity, to engage IMF on potential deficit Ghana ranked 62 of 125 countries in 2023 Global Hunger Index Oil tanker transits through the Suez Canal were down 23% last month compared with November, Kpler said in a note released Jan. 30. The drop was even more pronounced for liquefied petroleum gas and liquefied natural gas, which fell 65% and 73%, respectively. In product markets, flows of diesel and jet fuel from India and the Middle East to Europe, and European fuel oil and naphtha heading to Asia have been most affected. Asian prices of naphtha, a petrochemicals feedstock, hit the highest in almost two years last week on fears it would become tougher to source it from Europe. The impact of the Red Sea attacks is feeding through to oil prices via higher transport costs, which is encouraging refiners to go local where they can. Rates for Suezmax crude tankers from the Middle East to Northwest Europe have jumped by around half since mid-December, Kpler said. Global benchmark Brent crude is up around 8% over the same period. Meanwhile, the delivered cost of oil to Asia from the US, where production is surging, rose by more than $2 a barrel over a three-week period in January, according to traders involved in the market. “Diversification is still possible, but it comes at a higher price,” said Giovanni Staunovo, a commodity analyst at UBS Group AG. “Unless it can be passed onto the end consumer, it would cut into the margins of refineries.” The situation in the Red Sea isn’t expected to lead to a long-term rearrangement of oil flows, but it’s also difficult to see a resolution of the conflict in the near term. Instead, there’s a significant risk of more disruptions, particularly after the Houthi strike on a tanker carrying Russian fuel late last month. That attack was noteworthy as the Iranian-backed militant group had previously indicated that Russian and Chinese ships wouldn’t be targeted. “Geopolitics are not good for trade,” said Adi Imsirovic, director of consultancy Surrey Clean Energy. “If I was a buyer, I would be on my toes. It’s a hard time for refiners, especially Asian refiners, who need to be more flexible.”

- Advertisement -

The global oil market is looking increasingly local as militant attacks in the Red Sea and surging freight rates make supplies from closer to home more attractive.

A slump in tanker traffic through the Suez Canal is spurring the beginnings of a split, with one trading region centered around the Atlantic Basin and including the North Sea and the Mediterranean, and another encompassing the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and East Asia. There’s still crude moving between these areas — via the longer and costlier journey around the southern tip of Africa — but recent buying patterns point to disconnection.

- Advertisement -

Across Europe, some refiners skipped purchases of Iraqi Basrah crude last month, according to traders, while buyers from the continent are snapping up cargoes from the North Sea and Guyana. in Asia, a jump in demand for Abu Dhabi’s Murban crude led to a spike in spot prices in mid-January, and flows from Kazakhstan to Asia are down sharply.

- Advertisement -

Crude loadings from the US to Asia, meanwhile, plunged by more than a third last month from December, ship-tracking data from Kpler show.

The fragmentation will not be permanent, but for now it’s making it tougher for import-dependent nations like India and South Korea to diversify their sources of oil supply. For refiners, it limits their flexibility to respond to rapidly changing market dynamics and could eventually eat into margins.

“The pivot toward logistically easier cargoes makes commercial sense, and that will be the case for as long as the Red Sea disruptions keep freight rates elevated,” said Viktor Katona, lead crude analyst at data analytics firm Kpler. “It’s a tough balancing act choosing between security of supply and maximizing profits.”

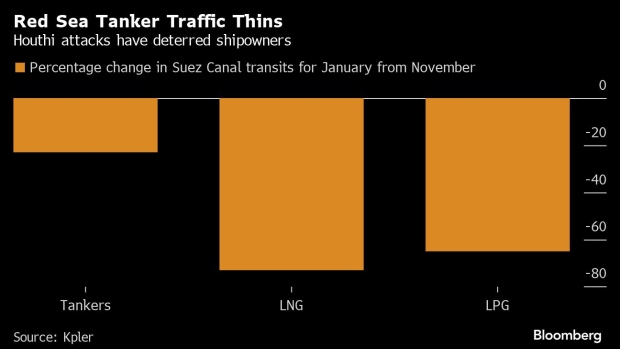

Oil tanker transits through the Suez Canal were down 23% last month compared with November, Kpler said in a note released Jan. 30. The drop was even more pronounced for liquefied petroleum gas and liquefied natural gas, which fell 65% and 73%, respectively.

In product markets, flows of diesel and jet fuel from India and the Middle East to Europe, and European fuel oil and naphtha heading to Asia have been most affected. Asian prices of naphtha, a petrochemicals feedstock, hit the highest in almost two years last week on fears it would become tougher to source it from Europe.

The impact of the Red Sea attacks is feeding through to oil prices via higher transport costs, which is encouraging refiners to go local where they can. Rates for Suezmax crude tankers from the Middle East to Northwest Europe have jumped by around half since mid-December, Kpler said. Global benchmark Brent crude is up around 8% over the same period.

Meanwhile, the delivered cost of oil to Asia from the US, where production is surging, rose by more than $2 a barrel over a three-week period in January, according to traders involved in the market.

“Diversification is still possible, but it comes at a higher price,” said Giovanni Staunovo, a commodity analyst at UBS Group AG. “Unless it can be passed onto the end consumer, it would cut into the margins of refineries.”

The situation in the Red Sea isn’t expected to lead to a long-term rearrangement of oil flows, but it’s also difficult to see a resolution of the conflict in the near term. Instead, there’s a significant risk of more disruptions, particularly after the Houthi strike on a tanker carrying Russian fuel late last month. That attack was noteworthy as the Iranian-backed militant group had previously indicated that Russian and Chinese ships wouldn’t be targeted.

he global oil market is looking increasingly local as militant attacks in the Red Sea and surging freight rates make supplies from closer to home more attractive.

A slump in tanker traffic through the Suez Canal is spurring the beginnings of a split, with one trading region centered around the Atlantic Basin and including the North Sea and the Mediterranean, and another encompassing the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and East Asia. There’s still crude moving between these areas — via the longer and costlier journey around the southern tip of Africa — but recent buying patterns point to disconnection.

- Advertisement -

Across Europe, some refiners skipped purchases of Iraqi Basrah crude last month, according to traders, while buyers from the continent are snapping up cargoes from the North Sea and Guyana. in Asia, a jump in demand for Abu Dhabi’s Murban crude led to a spike in spot prices in mid-January, and flows from Kazakhstan to Asia are down sharply.

Crude loadings from the US to Asia, meanwhile, plunged by more than a third last month from December, ship-tracking data from Kpler show.

The fragmentation will not be permanent, but for now it’s making it tougher for import-dependent nations like India and South Korea to diversify their sources of oil supply. For refiners, it limits their flexibility to respond to rapidly changing market dynamics and could eventually eat into margins.

“The pivot toward logistically easier cargoes makes commercial sense, and that will be the case for as long as the Red Sea disruptions keep freight rates elevated,” said Viktor Katona, lead crude analyst at data analytics firm Kpler. “It’s a tough balancing act choosing between security of supply and maximizing profits.”

Oil tanker transits through the Suez Canal were down 23% last month compared with November, Kpler said in a note released Jan. 30. The drop was even more pronounced for liquefied petroleum gas and liquefied natural gas, which fell 65% and 73%, respectively.

In product markets, flows of diesel and jet fuel from India and the Middle East to Europe, and European fuel oil and naphtha heading to Asia have been most affected. Asian prices of naphtha, a petrochemicals feedstock, hit the highest in almost two years last week on fears it would become tougher to source it from Europe.

The impact of the Red Sea attacks is feeding through to oil prices via higher transport costs, which is encouraging refiners to go local where they can. Rates for Suezmax crude tankers from the Middle East to Northwest Europe have jumped by around half since mid-December, Kpler said. Global benchmark Brent crude is up around 8% over the same period.

Meanwhile, the delivered cost of oil to Asia from the US, where production is surging, rose by more than $2 a barrel over a three-week period in January, according to traders involved in the market.

“Diversification is still possible, but it comes at a higher price,” said Giovanni Staunovo, a commodity analyst at UBS Group AG. “Unless it can be passed onto the end consumer, it would cut into the margins of refineries.”

The situation in the Red Sea isn’t expected to lead to a long-term rearrangement of oil flows, but it’s also difficult to see a resolution of the conflict in the near term. Instead, there’s a significant risk of more disruptions, particularly after the Houthi strike on a tanker carrying Russian fuel late last month. That attack was noteworthy as the Iranian-backed militant group had previously indicated that Russian and Chinese ships wouldn’t be targeted.

“Geopolitics are not good for trade,” said Adi Imsirovic, director of consultancy Surrey Clean Energy. “If I was a buyer, I would be on my toes. It’s a hard time for refiners, especially Asian refiners, who need to be more flexible.”

- Advertisement -