G20 economies should turn to reforms to improve growth amid policy tightening

The weak growth outlook amid heightened uncertainty, still-elevated global inflation, and limited fiscal space provides many challenges for policymakers. And while some IMF recommendations might, therefore, seem difficult at such a time, our report does highlight more upbeat consequences: disinflation, rebuilt buffers to help manage future shocks, and the prospect of stronger and more balanced growth.

- Advertisement -

Most Group of Twenty economies are likely to keep monetary policy appropriately tight to bring inflation back to target. Central banks will need to keep interest rates higher for longer as inflation remains persistently elevated—and easing too soon could undo hard-won progress to anchor inflation expectations.

This higher-for-longer environment for borrowing costs, however, portends sustained funding pressures for governments. That means governments will need to consolidate their finances to rebuild buffers and ensure that their debt is sustainable. Most G20 economies are poised to cut spending and boost revenues in the next few years, but in many cases IMF staff recommend even greater fiscal effort to ensure sufficient space to respond to future shocks and new fiscal challenges.

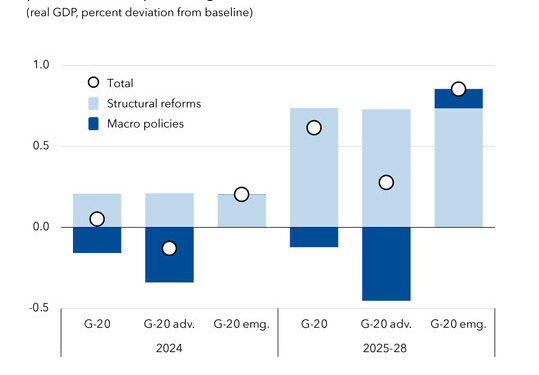

Amid the likely drag of both monetary and fiscal tightening, both advanced economies and emerging market and developing countries should consider structural reforms, such as those to make product and labor markets more efficient, to support economic growth. While the exact prescriptions will differ by country, recent IMF research shows significant potential benefits of so-called first-generation reforms in emerging market and developing economies that, in turn, can have beneficial spillovers for advanced economies.

As the Chart of the Week shows, pairing macroeconomic policy that’s tighter than currently planned in many economies—particularly advanced economies—with priority structural reforms can boost G20 economic output by as much as 0.7 percent over 2025-28 relative to current projections. That’s according to our latest report prepared for the group, whose members are responsible for about four-fifths of global gross domestic product.

|

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

While the recommended macroeconomic adjustments would weigh on output in the G20’s advanced economies in coming years—because of a tighter-than-planned fiscal consolidation—they would substantially reduce public debt burdens and trade imbalances among G20 economies. And the burden on output would be more than offset should the changes be accompanied by recommended structural reforms. The pace and composition of fiscal consolidation should protect of the most vulnerable people to ensure inclusive and equitable outcomes.

Our G20 report follows the latest IMF World Economic Outlook, which forecast growth will slow from 3.5 percent last year to 3 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year—a slight downgrade from July. Five-year-ahead projections are down from a peak of 4.9 percent a decade ago to 3.1 percent for 2028, the lowest such forecast since 1990.

The weak growth outlook amid heightened uncertainty, still-elevated global inflation, and limited fiscal space provides many challenges for policymakers. And while some IMF recommendations might, therefore, seem difficult at such a time, our report does highlight more upbeat consequences: disinflation, rebuilt buffers to help manage future shocks, and the prospect of stronger and more balanced growth.

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -