Oil’s Fall Into $60s Widens the Runway for the Global Economy to Make a Soft Landing

With global benchmark Brent crude falling below $70 a barrel for the first time since late 2021 on Tuesday, a key component of the energy shock that drove the worst inflation crisis in a generation is already benign enough to give policymakers a green light for interest rate cuts.

- Advertisement -

The world’s advanced economies might just have a new reason to hope for a firmer growth footing in the next year, if some of the most bearish forecasts for oil hit the mark.

With global benchmark Brent crude falling below $70 a barrel for the first time since late 2021 on Tuesday, a key component of the energy shock that drove the worst inflation crisis in a generation is already benign enough to give policymakers a green light for interest rate cuts.

- Advertisement -

But the prospect of a descent toward $60 a barrel in 2025, raised by forecasters from Citigroup Inc. to JPMorgan Chase & Co., and echoed on Monday by one of the world’s largest commodities traders, could further bolster the chances of the US and its peers weathering the effect of high borrowing costs without a damaging recession.

- Advertisement -

“The probability of pulling off a soft landing would increase — that applies to Europe as well as the US,” said Tim Drayson, head of economics at Legal & General Investment Management Ltd. in London and a former UK Treasury official. “On balance it would be a net positive for the world getting rates back down, and helping central banks get back to neutral.”

For monetary institutions poised to cut rates this month, the recent decline in oil prices has already opened the door wider to easing. Officials at the European Central Bank are set to deliver a second rate reduction on Thursday, while the US Federal Reserve is widely expected to start its own cycle of easing less than a week later.

The promise of $60 oil — at least for those who investors and policymakers who believe it — has the potential to further depress headline inflation rates and offer consumers a disposable-income boost. That’s a rare bright spot in a world fraught with risks ranging from possible trade wars, to the worry of what a Chinese deflation spiral might do to global demand.

“It’s very helpful, especially for central banks,” said Christof Ruehl, senior analyst at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “It takes pressure off inflation, which is exactly what central banks need now.”

Adjusted for inflation, oil is now at levels seen two decades ago, when Beijing’s commodities boom was just beginning. Analysts at JPMorgan and Citigroup expect prices to fall further next year, as subdued demand growth is overwhelmed by a flood of new supply.

Brent crude is “probably going to go into the $60s some time relatively soon,” Ben Luckock, global head of oil at Trafigura, said at the Asia Pacific Petroleum Conference in Singapore on Monday. Gunvor Group Ltd., another major trader, warned that oil markets are set to “worsen.”

Anemic demand is part of the equation, not least with the US economy losing momentum and China’s deflationary backdrop becoming ever more pronounced.

“It does point in the direction of the two largest economies in the world,” said Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis SA. China “is in structural deceleration, which is continuing. And then the US is coming up with the same kind of tone — maybe not structural but cyclical.”

Supply Growth

While the US economy shows signs of weakness, its petroleum industry remains in rude health.

- Advertisement -

Global oil production will swell by 1.5 million barrels a day this year and next — led by American shale fields — surpassing growth in world demand by roughly 50%, according to the International Energy Agency in Paris. This supply surge is one reason why prices have continued to wilt despite extended production cuts by Saudi Arabia and its allies in the OPEC+ cartel.

Such is the enduring importance of crude to global consumer prices that a swift decline to $60 a barrel — amounting to a decline of about $20 since July — would make a material difference.

The SHOK model devised by Bloomberg Economics suggests an immediate drop of that magnitude would remove 0.4 percentage point off inflation rates in the US and Europe in late 2024 and early 2025. For China, the decline would be half of that.

Its immediate stimulus effect for economic growth could be more muted than the impact on consumer prices.

Under the $60 scenario, the SHOK model anticipates little change to the US growth outlook from that outcome, and a 0.2 percentage point gain in the UK and the euro area.

“You’d see near-term impact on headline inflation — that would come through pretty quickly,” said Hetal Mehta, head of economic research at St James Place, and a former UK government economist. “The growth impact should be mildly supportive — if you have lower inflation.”

Households would notice the difference, said Drayson at LGIM. “There would be positives for the developed market consumer — it would help cool down inflation and boost real incomes,” he said.

The first major monetary institution to confront the changing oil backdrop will be the ECB on Thursday. Its officials are most focused on the dangers posed by services inflation, which is still running at more than double their 2% target, but the risks to growth are also shifting into view.

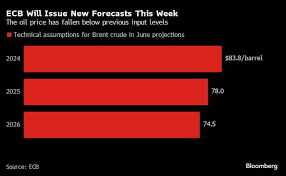

Cheaper crude will already have had an automatic impact on the quarterly forecasts they use to guide their judgment. Last time round, in June, officials factored in an assumption of $78 a barrel for 2025 — suggesting a $60 outcome would indeed make a serious downward impact on their inflation outlook if it were to materialize.

In the US meanwhile, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen declared on Saturday that the situation there “is what most people would call a soft landing.” But it’s the worry of a souring economy — along with the lessening of inflation risks — that is causing policymakers there to pivot to easing at their decision on Sept. 18.

TS Lombard Chief Economist Freya Beamish, who already sees a “soft landing” scenario holding in the US, suggested that there’s comfort to be had in the knowledge that the lower the cost of crude goes there, the more of a stimulus it might provide.

“That would hand back purchasing power to the US consumer,” helping to mitigate some of the cracks that are showing in the nation’s economy, she told Bloomberg Television.

Source:norvanreports.com

- Advertisement -