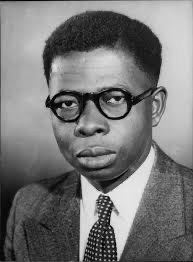

Ebenezer Ako Adjei, who died in Accra on 14 January 2002, could, in his lfetIme, unniquely be described as a “walking history of Ghana”. The 86 years that he was blessed to spend on this earth encompassed the most important historical periods in the life of Ghana.

There may have been others whose lifespans also covered equally crucial epochs in Ghana’s annals. But the difference between them and Ako Adjei is that he was a participating actor on the stage on which our national drama unfolded and reached its moments of greatest climax, and never a mere spectator.

Ako Adjei first entered the cauldron of politics in the “Gold Coast” (as Ghana was known before its independence) in 1947, after his return from Britain (where he had studied law and economics, as a post-graduate student from the USA.}

He had been very active in African politics in Britain and America, and thus was well known to the intellectuals and businessmen in the Gold Coast, when he returned home from England.

By 1947, many of the top educated Gold Coasters had begun a serious struggle to wrestle power from the British.

The most influential members of this nationalist group were, from the intellectuals’ side: Dr J. B. Danquah, the first West Africans to obtain a PhD from a British University, and a very prominent lawyer who had been dragging the colonial administration to the Privy Council in London, over a sensational murder case; and George Alfred “Pa” Grant, grandson of one of the earliest indigenous “merchant princes” in the Gold Coast and now a rich timber merchant based in Sekondi.

(“Pa” Grant’s grandfather had not limited himself to trading but had been a member of the Fanti Confederacy — an organisation that had worked with the pioneering, pro-self-government “Gold Coast Aborigines’ Rights Protection Society” (ARPS) — which was formed in 1897 — to oppose several measures proposed by the British to “alienate” or annex Gold Coast lands for the colonial administration..

It might have been thought that ‘Pa Grant and Dr J B Danquah – two gentlemen who were as “bourgeois” as they come – would have been accepted by the colonial administration and even co-opted into its ranks to stem the tide of nationalism that was sweeping the country.

But that is not how colonialism works. Its interests are primarily economic, and any local merchant who wanted to be more than a mere, petty agent of white traders — as Pa Grant did — and a brilliant lawyer who could draw rings around colonial bureaucrats who tried to extend their hold over “native lands” — as J.B. Danquah did — would be the object of their ire.

Thus, ironically, it was from the ranks of those whom Marxist analysts would probably regard as their best “natural allies” that the British administrators in the Gold Coast drew their fiercest enemies.

Why was this so?

AWAM!

By 1947, the selfishness of British rule had become obvious to everyone in the Gold Coast. Cocoa, the country’s largest industry, was in the hands of British merchant companies. Ghanaiansproduced the crop on their lands, swith their labour, but itsmarketing was entirely in the hands of British companies, such as the United Africa Company (UAC).

The price of the cocoa beans was decided in London and New York and handed down to Gold Coast farmers — without much reference to their costs of production, or their economic and social needs. Low as the price paid to the farmers on the world “commodities exchanges” usually was, thefarmers’ earnings from ther crp were diminished even further by the commissions subtracted from that price by the European “cocoa purchasing cmpanies” in the Gold Coast before the companies paid the farmers. British and European shipping companies (like Elder Dempster) also made huge sums of money carrying the beans to Europe and America, where it was manufactured into chocolates and sold at ten or twernty times the cost of the raw beans.

Simultaneously, the Gold Coast’s import trade was also being monopolised by European companies. There were quite a number of these, and it would have been thought that they would competeagainst one another and thus bring down the prices of the imports the Goldf Coast inhabitants needed (such as cloth, matches, sugar, kerosine and tinned foods). But no — the companies formed, instead, an importation cartel called “The Association of West African Merchants” (AWAM).

AWAM members harmonised their prices, so that if a Gold Coast resident wanted to buy a piece of cloth and thought the price demanded for it by, say, the retail moutlets of say, the United Africa Company (UAC) was too high and therefore he or she would try the shops of the Union Trading Company (UTC) or G. B. Olivant, or A.G. Leventis, that person would be wasting his or her time. For the price would be invariably the same in all the Europeasn shops! Even the relatively smaller Lebanese and Syrian retailers who took most of their stock from the European merchants, maintained uniform prices as soon as they became members of AWAM. That is why, to this day, the word “AWAM” has acquired the derogatory meaning, in Ghanaian English, of subterfuge or pretence.

(For instance, if you are conducting a love affair with a girl in your office, and in order to lead people off the trail, you pretend to be very hostile to her in public, anyone who knows the real truth would whisper to others behind the back of the lovers: “Don’t mind them — all that squabbling is AWAM!” Similarly, if a footballer, although hardly touched, nevertheless dives and writhes “in pain”, to try and fool the referee into nawarding a free kick, you will hear shouts of “AWAM!, AWAM!” from the spectators. People would understand that to mean “blatant feigning or fakery”!)